Palliative care in Poland

Opublikowano 15 listopada 2024 07:00

Katarzyna Cichosz: Professor, it was you who brought palliative medicine to Poland together with Cicely Saunders. Which year did you visit for the first time? What inspired you to visit Poland?

Robert Twycross: Cicely’s visit in 1978 was engineered by two Polish medical students, Joanna Pepke and Zbigniew Żylicz, as a result of visiting St Christopher’s Hospice in London two years earlier. Cicely lectured in Gdansk, Warsaw and Kraków. In Gdansk, at least partly as a result Cicely’s visit, the Pallotinum Hospice was subsequently set up by Father Eugeniusz Dutkiewicz.

Memory can play tricks but, from my passport, I see that my first visits to Poland were in 1988, 1990, 1991, and 1992. (There have been many more since!) The first one was the result of an invitation from (or in conjunction with) the Pallotinum Hospice in Gdansk. Father Eugeniusz met me at the airport in Warsaw and we drove for 2-3 hours to a convent for a residential conference attended by several dozen people. I don’t remember the exact number, nor the background of those attending.).

After the conference, I spent a short time in Gdansk as the house guest of Professor Julian Stolarczyk (a surgeon) and his wife, Dr Ewa Śmigielska-Stolarczyk (a radiologist and hospice volunteer) in Gdansk before returning home via Warsaw. I observed the work of the volunteer-staffed Pallotinum Hospice (mainly homecare with a few beds in a convent). The Stolarczyks subsequently translated a textbook I had written with Dr Sylvia Lack: ‘Leczenie terminalnej fazy choroby nowotworowej’ (published in 1991).

What inspired me to visit Poland? I had long been an advocate for palliative care, had written several textbooks, and had already been invited to lecture in several countries. I suspect Zbigniew Zylicz had a hand in engineering the invitation. In fact Dr Zylicz is an important and recurring figure in the story of palliative care in Poland, although by 1988 he was working in the Netherlands and subsequently in the UK and Switzerland.

Katarzyna Cichosz: By the end of the 1980s there were already hospices for adults in Gdańsk, Kraków and Poznań. With which of the Polish hospices did you start your cooperation?

Robert Twycross: At some point during those first four visits I visited these three cities and lectured in Warsaw as well. I first met Professor Jack Luczak from Poznan in Milan in 1988 at the first European Conference on Palliative Care. This led to an invitation in 1990 to lecture to the medical fraternity in Poznan before going with Jacek to a small conference centre in Katowice to jointly run a 5-day course for doctors from around Poland. Jacek, as Head of the Palliative Care Clinic of the Oncology Department of the Medical University of Karol Marcinkowski, had already established an expanding hospice and palliative care programme there, and was determined to train doctors from around Poland and in Eastern European countries.

This led to an accord with Sir Michael Sobell House (in one of the University Hospitals where I worked in Oxford), and annual residential courses run jointly with the team in Poznan. These courses were never in the same place and accommodation was typically fairly basic. In 1991, we ran the course near Slezin, a coal mining town. We stayed in brick huts in the summer holiday camp for miners and families - fairly bleak facilities. Even from 1990 we were accompanied by one or two nurses who taught about more general topics, such as care of the family and bereavement.

After 1994, my place was taken by my colleague, Dr Michael Minton. Released by Poland, albeit temporarily, I was able to spend time helping on courses in India, as well as in Argentina, and elsewhere. In Oxford, throughout the 1990s, we ran a 4-week International Summer School mainly for selected doctors and nurses from countries actively developing palliative care, including Poland. Several leading doctors in Poland today attended one of those Schools.

Katarzyna Cichosz: What kind of problems was Polish palliative care facing at the time?

Robert Twycross: Financial support from the Ministry of Health became available only in 1993. It was a significant step forward but, then as now, the available funds have always been less than optimal. A lack of trained staff was obviously also a key limiting factor in the early years, not helped by the absence of a palliative care module in the undergraduate training programmes for medical students, nurses, and other health professionals.

Katarzyna Cichosz: What were our strong points?

Robert Twycross: Looking back over 30 years, it is indeed time to celebrate how much palliative care has progressed in Poland, including the establishment of several university Departments of Palliative Care, and two Polish palliative care journals. Many peple are responsible for what has been achieved (see In Solidarity: Hospice-Palliative Care in Poland available from www.hospicefoundation.eu). However, from an international point of view, the contribution of Professor Jacek Luczak has been second to none. It was my privilege, and that of my colleague Michael Minton, to be involved in many of the early educational events organized by Jacek, and thus meet and get to know the second generation of palliative care pioneers, now the leaders in your country. The Polish Association for Palliative Care, and more recently the Polish Palliative Medicine Society and Polish Palliative Care Nursing Society, have all been important catalysts.

Katarzyna Cichosz: You also worked with the WHO. How did this help in development of palliative care worldwide?

Robert Twycross: In 1988, Sir Michael Sobell House in Oxford became the WHO Collaborating Centre for Palliative Cancer Care, with me as its designated Head. This obviously gave me a greater ‘visibility’, although as the author or co-author of several textbooks, as leader of courses both in Oxford and in the USA, and having been involved in the WHO Pain and Palliative Programme since the early 1980s, I was already fairly well known in the palliative care world. My introduction to India in 1991 was certainly through my WHO connection.

Katarzyna Cichosz: You visited many countries and witnessed the process of palliative medicine growth worldwide. Would you like to share your observations with us?

Robert Twycross: My role was catalyst and support to local champions. Success depended on them, not me. Some professional links inevitably led to greater success than others. The International Summer Schools we ran in Oxford for about 30 hand-picked doctors and nurses from many different countries (but always with six from India) was also important in the training for those we hoped would become the future leaders in their own countries.

Whether in Oxford or abroad, the emphasis was always on holistic care – the need to address psychological, spiritual and social issues as well the more obvious physical ones. Communication skills training was always a key feature; and the need for a sense of urgency, a methodical approach to symptom management (EEMMA, Evaluation, Explanation, Management, Monitoring, Attention to detail). Teaching about management was not restricted to pharmacotherapy but included ‘correct the correctible’ and non-drug treatments. The importance of multidisciplinary teamwork (TEAM, Together Everyone Achieves More), and an understanding of ethical issues in end-of-life care.

However, what developed locally depended not just on enthusiasm and commitment, but also on financial resources and support by the community and local media. To the extent that those receiving training were able to achieve this – usually with a group of enthusiastic volunteers – so success would follow. Thus, as I said above, I was just a catalyst and support: the hard work was done by local people. But remember: ‘‘The anger in compassion is a catalyst for change’ and ‘Success is no accident. It is hard work, perseverance, learning, studying, sacrifice and most of all, love of what you are doing.’

Katarzyna Cichosz: You have also helped to develop palliative care in India. What specific traits does it have there?

Robert Twycross: The challenges facing the development of palliative care in India have been and still are massive. It is a vast country with a population of over one billion, little more than a handful of some 30 States and Union Territories have a Palliative Care Plan, availability of morphine is still very patchy, poverty is ripe, distances are relatively big, and trained personnel are relatively few. Thus, although much has been achieved in the last 30 years, much still remains to be done. At most, it is estimated that <5% of those who need palliative care are able to access it.

Obviously, the central focus of palliative care is the same the world over, namely, to provide holistic person-centred care of patients with incurable progressive disease, and their families. However, the scope of palliative care tends to be country-specific, depending on local needs and the availability of care for those with chronic disability more generally.

Initially palliative care tends to be limited mostly to the care of end-stage cancer patients with just weeks or a few months to live. I have the impression that, in Poland, this is probably still the norm – with one or two notable exceptions where the service has been specifically expanded to include patients with end-stage respiratory and/or end-stage heart failure.

In England in the 1980s and 1990s, a number of hospices/palliative care services set up dedicated lymphoedema clinics for both patients with cancer and those with congenital or acquired lymphoedema from other causes. More recently, in Moldova, the Angelus Hospice in the capital, Chisinau, has set up the only support service for ostomy patients in the whole country; and, in Russia, chronic post-stroke care and long-term ventilator support are officially linked to palliative care services.

In Kerala in South India, particularly in association with the Neighbourhood Network in Palliative Care, services have spread even more broadly:

- end-stage progressive disease, e.g. cancer

- stable chronic disorders, e.g. paraplegia

- fluctuating chronic disorders, e.g. sickle-cell disease, lymphoedema

- slowly progressive diseases, e.g. peripheral vascular disease, HIV/AIDS.

Some Networks even stretch to selected patients with chronic psychiatric disorders.

Perhaps even more surprising is the initiative in Chandigarh in North India. Here there is a flourishing palliative care service comprising home-care, outpatient clinics and hospice beds, plus a project for children with special needs:

‘We realised when we went for home visits to the slums that these children were not cared for as they were from the poor strata of the society and the parents could not afford to take them to the special schools. So we have adopted six slums, and a Special Instructor and Physiotherapist go and visit the children at home and teach them. From volunteers, we try and provide them with tricycles and braille slates, books etc.’ (Patel F, personal communication).

Katarzyna Cichosz: What sort of challenges is palliative medicine facing in today’s world?

Robert Twycross: It is now accepted that all people dying from any form of end-stage disease should be able to access palliative care, and that it should been seen as an integral component of ‘universal health coverage’. However, there are many factors – and not just financial – which still work against its provision and delivery. For example, there will always be the need to contend with the ‘distaste’ many health professionals feel when confronted with end-stage disease, and their reluctance to change the focus of care from disease control to comfort. Linked with this is the inability of many health professionals to engage sensitively and skilfully in discussions about impending death.

In addition, today, the underlying values of most national healthcare services are incompatible with compassion and caring. Broadly speaking, the values of healthcare systems tend to be competition, rationalization, productivity, efficiency, and even profit. In other words, healthcare has been ‘industrialized’, and there is little room for ‘whole-person’ care. All too often this leads to emotional exhaustion and cynicism in the professional carers. Thus, the long-term challenge of providing high quality palliative care should not be under-estimated.

Palliative care is person-centred, not disease-focused. The goal is improvement in quality of life, not quantity. Attention to detail in every aspect of care is crucial for success. Palliative care should be seen as a partnership between experts. In relation to the disease process, the clinicians are the experts but, in relation to the impact of the illness, the experts are the patient and family. It is vital to recognize this because, through listening to their story and their problems, the patient and family begin to shift from being passive victims to empowered persons. For this, good communication skills are essential. A sense of urgency and deep compassion are also necessary, stemming from the attitude expressed long ago by Cicely Saunders, founder of modern Hospice and Palliative Care, and lover of Poland:

‘You matter because you are you,

you matter to the end of your life.

And we will do all we can, not only to help you die peacefully

but to live until you die.’

Katarzyna Cichosz: What would you like to tell doctors, nurses and carers starting their work with dying people?

Robert Twycross: The word ‘compassion’ literally means to ‘suffer with’. Compassion is not foremost about finding a solution. Compassion is being willing to accompany someone when there’s no solution to their predicament. At its deepest and broadest, compassion says, ‘There’s nothing that I will not face with you, there’s no suffering you can experience that will scare me away, there’s no pain you may have to bear that will stop me walking besides you every step of the way.’ Looked at in this way, you can see that caring for the dying, and supporting their families, will not be easy – far from it. A young doctor who had spent three months at Sobell House as part of his postgraduate training wrote to me several years after he had been in post as a general (family) practitioner. He said, ‘Since coming here I have looked after several dying patients. I still find it very demanding but very rewarding’. That is the inescapable paradox at the heart of palliative care.

‘Survival strategies’ will be necessary if you are going to survive longterm in palliative care. These strategies will differ from person to person, and are discussed in the literature on resilience. But one universal essential is teamwork - the fuel that allows ordinary people to achieve extraordinary results.

You will, I hope, gain much support from the attitudes of and interaction with your colleagues, e.g. at staff handovers, multidisciplinary team meetings, and ‘death reviews’. Mentoring and, sometimes one-to-one psychological support, may also be necessary. Maintaining a healthy work/leisure balance is crucial, even though often difficult to achieve on a day-to-day basis. Palliative care should never be seen as a strict ‘9am–5pm’ job; it is a professional calling. Adequate holidays (without access to emails and mobile phone!) are critically important. Take courage! The rewards of palliative care in terms of personal development are great, leading to ‘broader shoulders’ but without a ‘thicker skin’, and a greater ability to work without knowing all the answers.

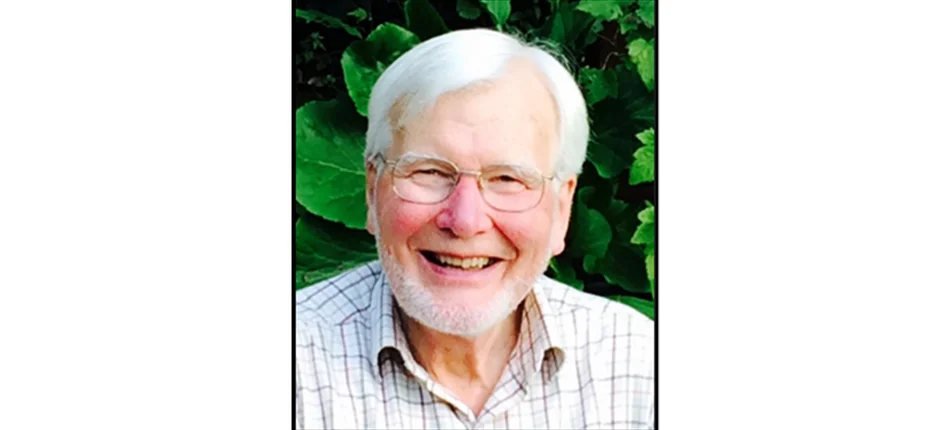

Robert Twycross

Emeritus Clinical Reader in Palliative Medicine, Oxford University, UK

Tematy

Robert Twycross